Information About Academic Gowns

Academic gowns are descended from the cappa clausa (closed cloak) of the clergy who taught at early medieval universities and whose garments were recognizable as a distinctive scholastic fashion by the 14th century. Reflecting the worldview of the Renaissance, academic gowns later began to be worn open and became more decorative, sewn from colorful fabric with fur or silk facings, embroidery, and distinctive long sleeves.

The 1895 Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume specified three types of gowns. Traditionally each gown was decorated with fluted fabric in the front, pleated fabric around the yoke, and a braided loop and button on the rear of the yoke that would help support the weight of the hood. Black was the color dictated by the Code, but by 1898 Cotrell & Leonard were providing customers with gowns that were blue, purple, dark green, gray, and white. These colored gowns were rare – black was the most popular choice for colleges and universities.

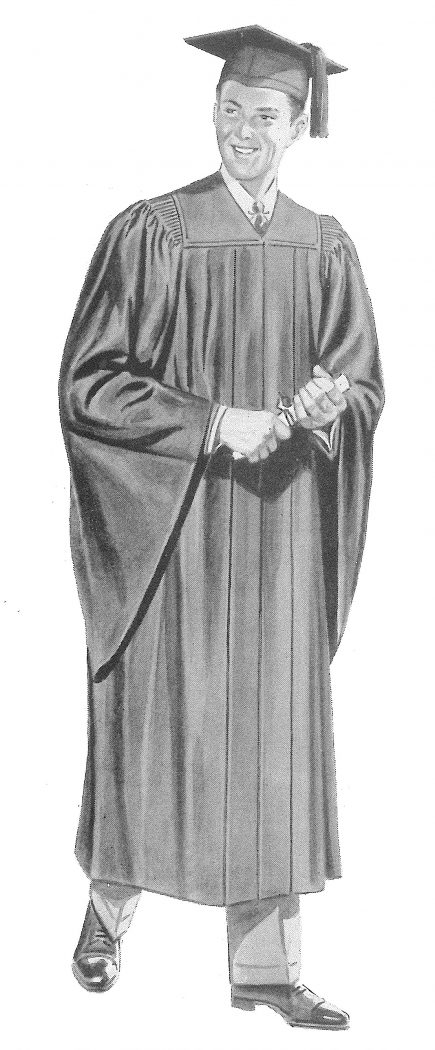

Bachelor’s Gown

The design of the American bachelor’s gown was based on the Oxford Bachelor of Arts gown.

According to the 1895 Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume, the gown would be tailored from black “worsted stuff” (usually a tightly woven wool/cotton blend) and would have long pointed sleeves. It was tailored from inexpensive fabric and worn closed in the front as a way of encouraging collegial uniformity and equality, hiding the clothing worn under the gown (the “sub fusc”) that would normally indicate differences in class, status, or wealth.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, college and university students would wear a bachelor’s gown to special events during their four years at school. At a few colleges they were worn to daily classes. At commencement undergraduates would receive a bachelor’s hood. Bachelor’s hoods were never very common – the expense was considered too great for a garment that would be worn only once. The Great Depression drove the final nail into that coffin, so today very few schools use bachelor’s hoods, and undergraduates commence in their bachelor’s gowns only.

Bachelor’s gowns are commonly used at American high schools and Junior Colleges. Instead of black, the gowns are tailored from fabric in one of the school colors of the high school (blue, maroon, gold, etc.), or in gray for Junior Colleges.

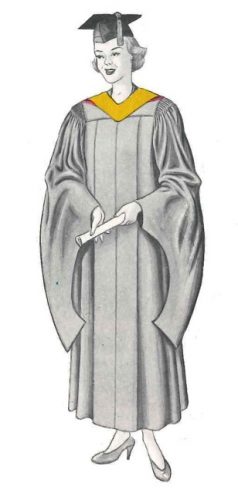

Master’s Gown

According to the Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume the master’s gown should be tailored from black silk and worn open. The wearer’s arms exited the sleeves at the elbow, and the end of the long closed sleeves had a crescent-shaped cutout at the rear of the sleeve that echoed the crescent-shaped cutout on the liripipe of the master’s hood. Some gown manufacturers placed this crescent-shaped cutout at the front of the sleeve.

The design of the American master’s gown was derived from the Master of Arts gown worn at Oxford University, except that Oxford’s sleeves have the crescent-shaped cutout at the front.

The sleeve design of the master’s gown required a jacket to be worn underneath, otherwise the wearer’s bare arms would show and create an awkward appearance. So in 1960 the American Council on Education’s Academic Costume Code moved the opening of the master’s sleeve from the elbow to the wrist and permitted the gown to be worn closed. The long sleeves now hang from the wrist and the crescent-shaped cutouts have lengthened to the entire front of the sleeve.

For historical reasons that can be traced to the medieval guilds, the Master of Fine Arts degree is unique among master’s degrees in that it is a terminal degree. Today the traditional master’s gown of the pre-1960s style is sometimes used by faculty with an MFA as a way to distinguish their terminal degree from standard (non-terminal) master’s degrees. This gown is combined with a doctoral hood and a mortarboard with a golden tassel.

Yale University authorizes the opposite – Masters of Fine Arts wear a doctoral gown with a master’s hood. This alternative approach is not recommended for the MFA because it creates an ensemble that is confusingly similar in appearance to the regalia worn by faculty with doctoral degrees.

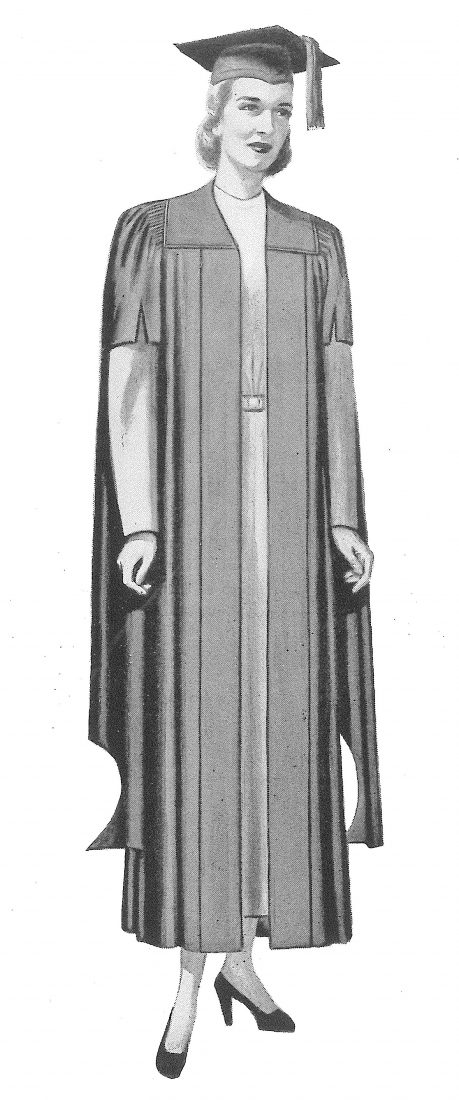

Doctoral Gown

The basic shape of the American doctoral gown is based upon the doctoral gown used at Oxford University.

According to the Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume, the American doctor’s gown should be tailored from black silk and have black velvet facings and three black velvet bars on each of the large, bell-shaped sleeves. Like the master’s gown, the doctoral gown was worn open in front.

As an alternative to black velvet facings and sleeve bars, one could use colored velvet that matched the velvet Faculty color edging of one’s hood. This tended to be a popular option for professors with Faculty colors that were dark and did not create too much contrast with the black gown.

By 1898, a third option was to use black facings with the outer inch in the Faculty color and the sleeve bars divided half black/half Faculty color. This third option was not popular and few gowns with facings and sleeve bars divided in this style have survived.

When Princeton University adopted the Intercollegiate Code in late 1895 or early 1896, it stipulated that the doctoral sleeve bars would be about one inch in width and three inches apart. No specific length was cited; many early gowns have quite lengthy bars of as much as 18 inches. The university also described the velvet facings of the doctor’s gown as being three inches in width.

Most manufacturers used more generous dimensions. Doctoral gown facings were typically four to five inches in width, and sleeve bars were 1½ to two inches in width but had shortened to between 14 and 15 inches in length by the 1930s.

The earliest doctoral sleeve bars were squared-off at each end, but by 1898 the ends of the bars were often triangular in shape.

After 1960 the doctor’s gown was usually tailored to be worn closed in front – much to the discomfort of faculty in warmer climates.

Unique Gown Styles

Today, many colleges and universities have adopted “custom academic regalia”. This can mean specially designed doctoral gowns, as at Stanford University and Vanderbilt University, but more commonly this term refers to gowns tailored from fabric in the school colors of the institution. For more on this subject, see the 2009 Transactions of the Burgon Society article by David Boven entitled “American Universities’ Departure from the Academic Costume Code”, here.

Tailoring Details