Information About Academic Hoods

Hoods in the medieval period were lined with fur in the winter and colorful silk in the summer and were a part of academic dress by the 16th century, having fallen out of fashion among laymen after the introduction of window glazing in the middle of the 1400s.

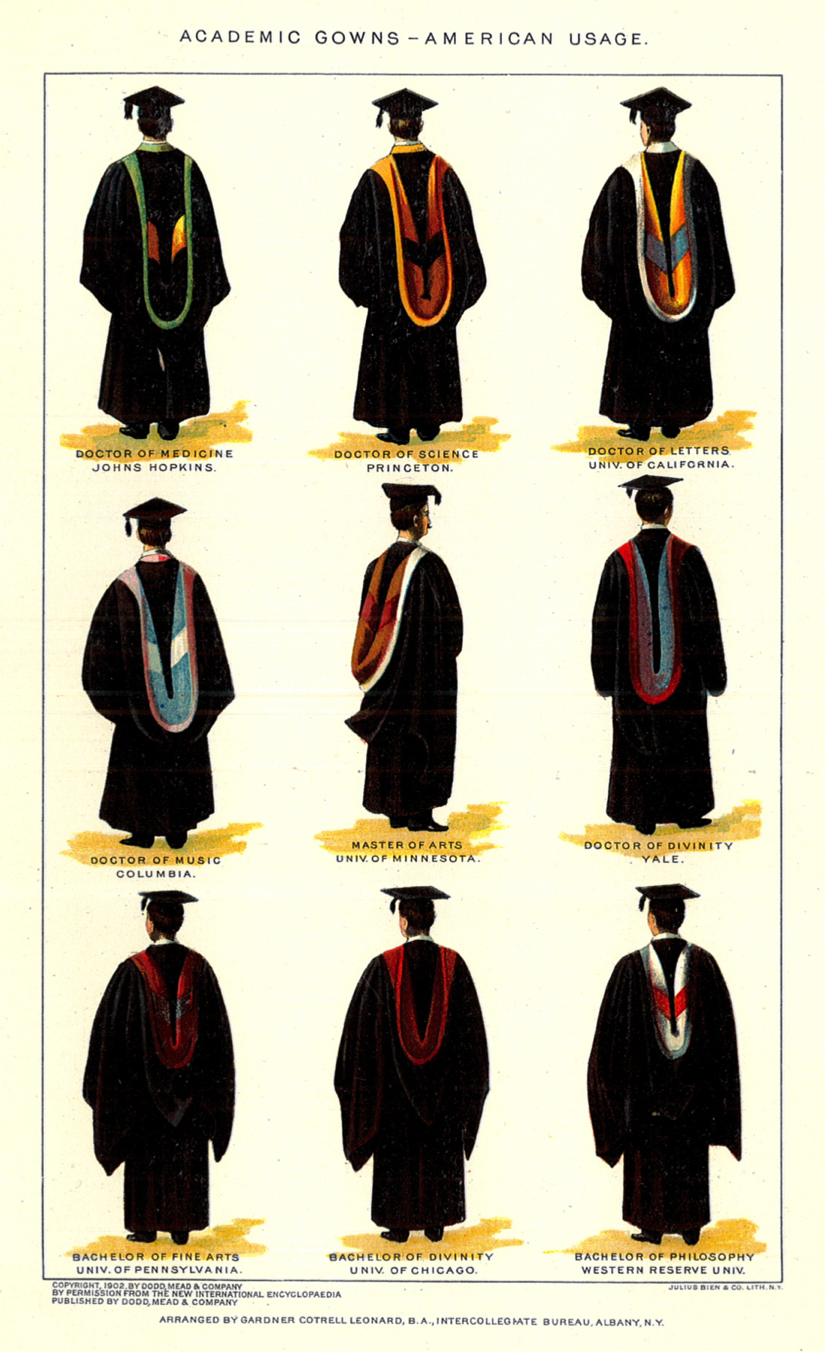

It was the academic hood that most fully achieved the goal of the Intercollegiate Commission of Academic Costume to create a sartorial taxonomy that indicates the wearer’s degree and the college or university that conferred the degree.

The technical advisor to the commission was Gardner Cotrell Leonard, President of the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume and the head of the academic costume division of his family’s Cotrell & Leonard firm in Albany, New York. After the Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume was ratified on 16 May 1895, Leonard described it as being

a statute that might be adopted by any institution, classifying the types of gowns, and doing a valuable constructive work in the sections which arranged a scheme of pattern and coloring to make the hood a plain badge of the degree, be it Bachelor, Master or Doctor; of the department of learning, be it Arts, Philosophy, Law, Theology or other; and of the institution granting the degree or with which the holder was then connected.

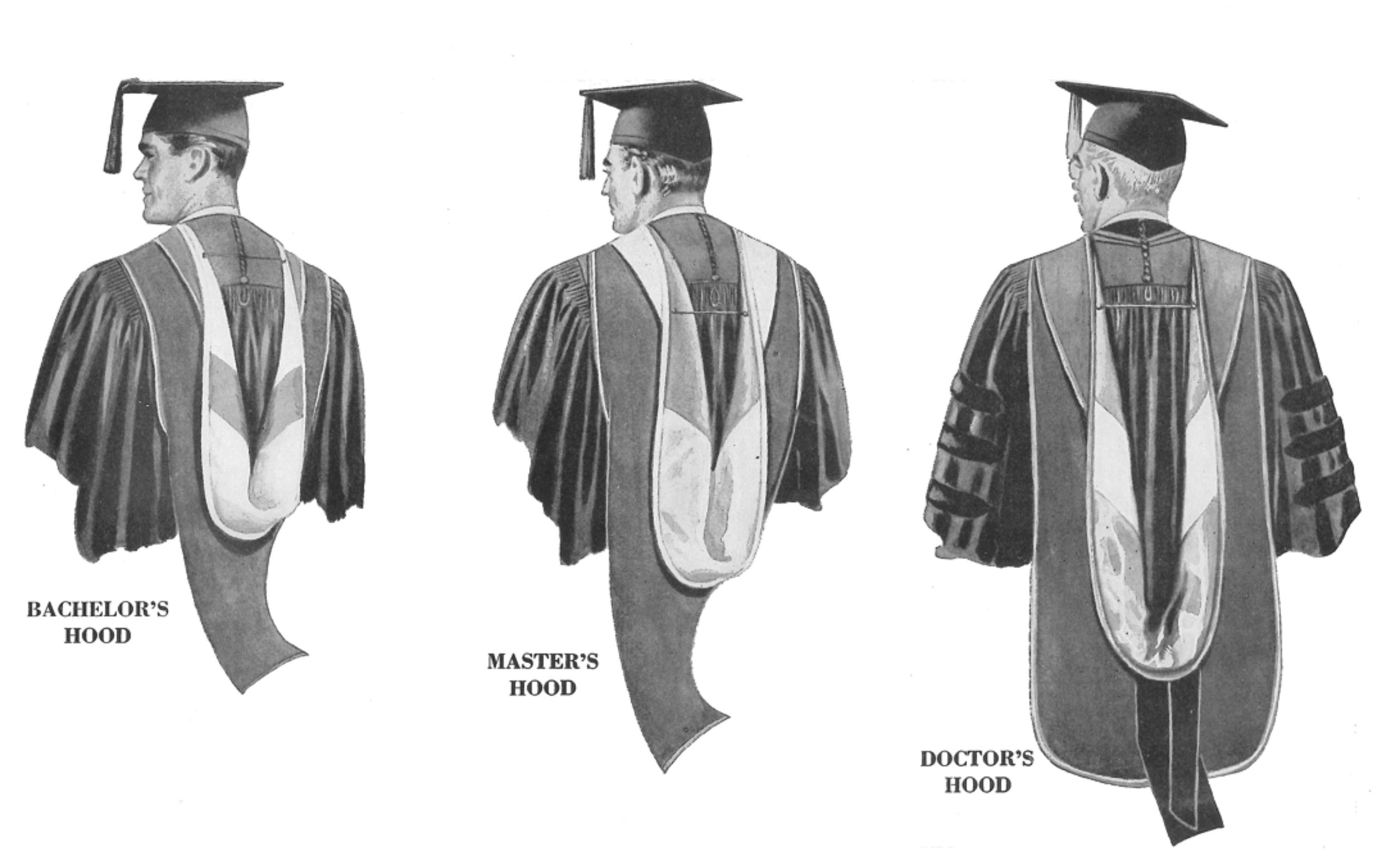

The level of the degree is communicated by the length and shape of the hood. A bachelor’s hood is three feet in length and is of “simple” shape, which means it has a cowl and liripipe (the “tail”) only. Due to cost, the bachelor’s hood was not commonly worn, an omission that continues today. A master’s hood is also of simple shape and was originally four feet in length. In 1902 Harvard University stipulated that its master’s hoods would be 3½ feet in length, and within a few years this became the standard length for all master’s hoods tailored in the United States. The doctor’s hood is of full shape, which means it has a cape (or “panels”) on either side of the cowl, and is four feet in length. Originally the shape of the cape was fully rounded at the bottom, but by 1902 manufacturers had begun to flatten the curvature of the bottom of the cape.

Whether simple or full, the American hood was based on the Oxford University Bachelor of Arts hood of the 1890s, with a “split salmon” shape that allowed the cowl to be folded back to display more of the lining than was typical of British hoods. On American hoods, a black cord and button are used to keep the two halves of the hood lining in close proximity.

The hood is worn around the neck, held in place by a black cord that can be attached to a button on the front of the wearer’s shirt.

The liripipe of the bachelor’s and master’s hoods have crescent-shaped cutouts on the trailing edge. This shape is echoed in the cutout at the bottom of the sleeves of the master’s gown. The liripipe of the doctoral hood is rectangular, with no crescent-shaped cutout, and the rounded shape of the hood’s cape echoes the rounded, bell-shaped sleeves of the doctor’s gown.

Today the Burgon Society uses the Groves Classification System to describe various types of academic hoods. The American doctoral hood is classified as pattern [f14]. The American bachelor’s and master’s hoods are not assigned a unique pattern in the Groves system; they are an amalgamation of the contemporary Oxford University simple [s1] and Wales University simple [s5] patterns.

The exterior of the hood is tailored from the same black “worsted stuff” (bachelor’s) or silk (master’s and doctor’s) fabric as the gown, but the hood is lined with silk in the colors of the college that conferred the degree. The 1895 Intercollegiate Code stated that the hood’s lining colors could also represent the college or university at which the faculty member was employed, but this practice was never common and began to fall out of favor in the 1930s.

The school colors in the hood lining are divided using various heraldic patterns so that each college or university that registered with the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume was assigned a hood lining pattern unique to that school. About a quarter-inch of this silk lining would be carried over the edge of the doctoral cape so that the shape of the black cape could be seen against the black gown; better made hoods would edge the cape with cording (or “piping”) in one of the colors of the hood lining.

According to the 1895 Intercollegiate Code, the hood should be edged with silk, satin, or velvet in a color that would indicate the “Faculty” of the degree title as it appears on the diploma of the wearer. In practice, velvet was almost always used, probably because it provided a nice contrast to the silk lining fabric and complemented the velvet facings and sleeve bars on the doctoral gown. Initially the 1895 Code said that this trim should be no wider than six inches, but the University of Pennsylvania and Yale University stipulated that it be no wider than four inches. Princeton’s regulations (written in late 1895 or early 1896) were more specific; there the width of the trim indicated the level of the degree: bachelor’s hoods used velvet edging two inches wide, master’s hoods used velvet edging three inches wide, and doctoral hoods used velvet edging five inches wide. These widths were quickly adopted by most academic hood manufacturers, although some doctoral hoods were trimmed with velvet four to 4½ inches wide to avoid giving a disproportionately exaggerated appearance to the hood edging.

Due to a misinterpretation of a photograph and caption in a 1939 pamphlet entitled The Story of Caps and Gowns written by Helen Walters and published by academic costume manufacturer E.R. Moore, some academic costume manufacturers and at least one or two colleges thought that the heraldic pattern in the academic hood lining signified the level of one’s degree. One example of this misinterpretation can be seen in article entitled “To Increase Your Enjoyment of Commencement Pageantry” in the May 1959 edition of the Southern California Alumni Review, which erroneously stated that two chevrons indicated a Bachelor’s degree, a parti per chevron division indicated a Master’s degree, and a single chevron indicated a Doctor’s degree. Fortunately, this misunderstanding of the Intercollegiate Code never became widespread.

As seen in the photograph to the right, a feature unique to American academic hoods is a cord used to pull the two sides of the hood lining together so that the colors and heraldic pattern are more clearly displayed. Originally incorporated by Gardner Cotrell Leonard on the hoods produced at Cotrell & Leonard, this cord quickly became standard on hoods produced by all American academic costume manufacturers. The cord also helps to keep the hood on the wearer’s shoulders and close to the neck. Photographs in early Cotrell & Leonard catalogues show that Leonard intended the cord to be passed through the braided loop and button on the back yoke of the gown, to help prevent the hood from slipping down the wearer’s back, due to its weight. But this method of wearing the hood cord was soon forgotten and today the braided loop and button on the gown’s yoke is merely a vestigial decoration.

Initially, the Code also permitted professors who had earned more than one doctoral degree to divide the velvet trim on their hood and gown to display two or more Faculty colors, but this was rarely seen in practice. It was officially proscribed by the 1935 Academic Costume Code as “bad form”, because “the imagination dislikes to contemplate the results to which such a proposal might lead if, as often happens, the wearer held doctorates in three or more subjects”.

Approving new Faculty colors and assigning a unique hood lining pattern to every college and university that requested one were the responsibilities of the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume. Gardner Cotrell Leonard, the Bureau’s president until his death in 1921, said that the Intercollegiate Commission had given the Bureau this authority “to avoid confusion, easily arising from independent action in the choice of colors representative of the degrees, or in the combination of colors in hood linings.”

Since there were hundreds of colleges and universities in the United States, assigning a unique hood lining pattern to each was a herculean task. Unfortunately, Leonard’s successors at the Bureau were not interested in maintaining this system, and very quickly it fell into disarray. But even while Leonard was alive the Intercollegiate Bureau began to cut corners. Synonymous color descriptions (like “dark blue”, “navy blue”, “Yale blue”, and “deep blue”) were often used to hide the fact that two or more schools had been assigned hood lining patterns that were, in fact, identical.

By the early 1930s, the Bureau seems to have stopped assigning unique hood linings to schools that only offered bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Only colleges and universities with doctoral programs would be assigned individualized hood lining patterns, as these were the only hoods that would be used professionally, by faculty.