Faculty Colors

By the 15th century it was common for professors to wear a particular color to show their affiliation with the medieval “lower” Faculty of Arts (the Liberal Arts, sometimes called the Faculty of Philosophy) or with one of the “higher” Faculties of Canon Law, Civil Law, Medicine, or Theology. “Faculty” was the term that originally referred to the undergraduate or graduate academic collegium that determined the requirements for the degree and whether those requirements had been met. Today this historical meaning of the term “Faculty” is most closely synonymous to what we would call a “School” or “College”, not to the professors within the collegium. The association with an undergraduate or graduate Faculty and a particular color differed among the universities in Europe, but some common “Faculty color” choices included black or white for Theology; blue for Arts/Philosophy; and scarlet for Canon Law. A graduate of one of these universities would be granted a degree title indicating his affiliation with the Faculty that conferred the degree and his mastery of that pedagogical subject, as in “Doctor of Theology”, or “Master of Arts”.

Academic degrees in the United States use a binomial or trinomial nomenclature. At a minimum there is always the degree level (bachelor, master, or doctor) and the degree “Faculty”. This binomial nomenclature is used on the diploma the student receives when he or she graduates.

TRADITIONAL DEGREE NOMENCLATURE

“[level] of [Faculty]”

“Bachelor of Music”

“Master of Fine Arts”

“Doctor of Philosophy”

Most degree titles do not include the major subject of the degree on the diploma; this information is found in the student’s transcript. But in a “tagged” degree the major subject is added to create a trinomial degree title on the diploma.

DEGREE NOMENCLATURE FOR A “TAGGED” DEGREE

“[level] of [Faculty] in [major subject]”

“Bachelor of Science in Nursing”

“Master of Arts in Theology”

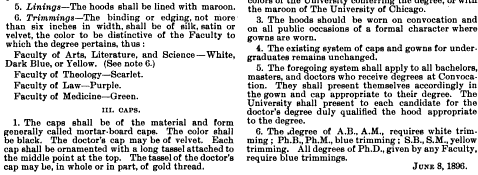

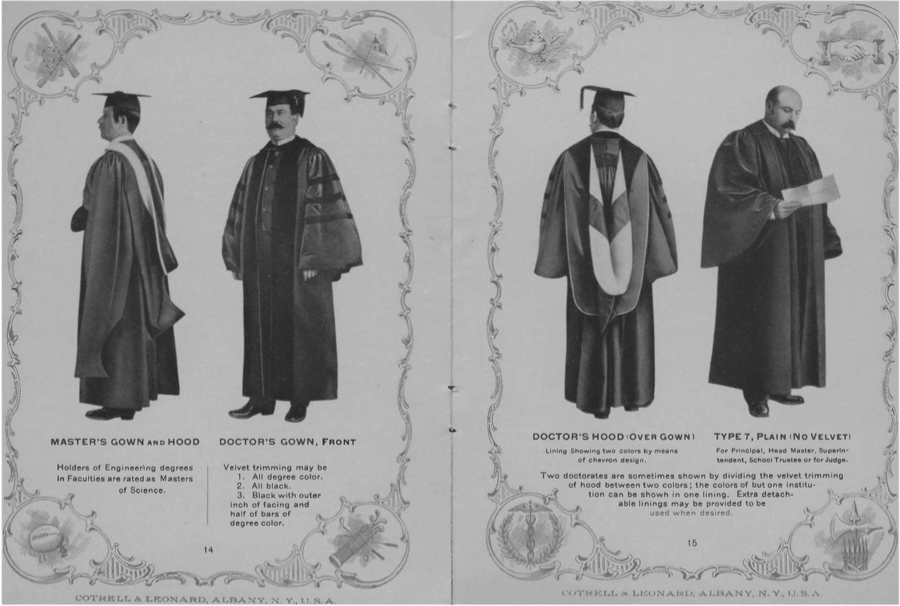

The members of the 1895 Intercollegiate Commission of Academic Costume wanted “the cap and gown and hood [to indicate] the degree of the wearer and the faculty under which it was obtained” so that an observer could look at a person’s cap, gown, and hood and understand that the graduate had earned, for instance, a Bachelor of Arts degree, or a Master of Science degree, or a Doctor of Medicine degree. The commissioners decided that the style of gown and length and style of hood would communicate the level of the degree, while the color of the velvet edging on the hood would communicate the Faculty of the degree, as would the velvet facings and sleeve bars on the doctoral gown if black was not used.

Professor Ogden Nicholas Rood and Mr. Gardner Cotrell Leonard acted as advisors to the commissioners on this matter. Rood was a Columbia University professor of Physics who specialized in light, chromatics, and photography, and whose color theories had deeply influenced the French Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat. Rood was also an amateur painter. Leonard was head of the academic costume department at Cotrell & Leonard, his family’s clothing store in Albany, New York. He was also the president of the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume, an organization Leonard created in 1887 to collect information about academic regalia and promote its use in America. Leonard wrote that the academic hood as envisioned by the 1895 Intercollegiate Commission was “a plain badge of the degree, be it Bachelor, Master or Doctor; [and] of the department of learning, be it Arts, Philosophy, Law, Theology or other”.

With the help of Professor Rood and Mr. Leonard, the Intercollegiate Commission on Academic Costume authorized eight Faculty colors (sometimes called “degree colors” because the wording of the degree determined the color) when they composed the Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume in May of 1895. These first Faculty colors represented the most common degrees being conferred at American colleges and universities at that time.

Arts and Letters

Fine Arts

Law

Medicine

Music

Philosophy

Science

Theology

white

brown

purple

green

pink

blue

gold yellow

scarlet

It is important to stress that the commission members intended these eight Faculty colors to encompass a multitude of similar degree titles within the traditional liberal arts and sciences. So, for instance, the brown of Fine Arts would indicate not only the Bachelor and Master of Fine Arts degrees, but also the Bachelor of Painting degree and the Master of Architecture degree. The golden yellow of Science would signify the Bachelor, Master, and Doctor of Science degrees, but also the Doctor of Chemistry degree and Bachelor and Master of Engineering degrees.

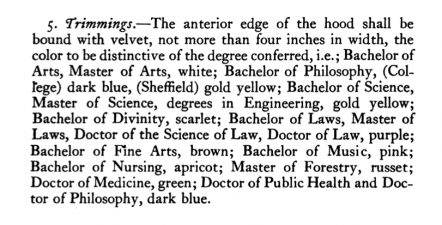

The Intercollegiate Commission entrusted Mr. Leonard’s Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume with the responsibility of authorizing further Faculty colors that might be added to the Code. This happened with increasing frequency in the early 1900s as land grant colleges and universities began to create new Schools and Colleges with professional and technical degree programs, each with a unique degree title that included the name of the profession or specialization: Bachelor of Physical Education, Master of Nursing, Master of Forestry, Doctor of Optometry, and so on. As a result, between 1895 and 1961 the Bureau would approve a total of 34 Faculty colors. However, five of those 34 colors were discontinued in 1959 or 1960 because the degrees they indicated were rarely conferred. These included two degree colors that are known to have been officially authorized (Humanics and Philanthropy) and three degree colors whose official authorization status is less certain (Naprapathy, Political Science, and Retailing).

On the following chart the adoption date and deletion date (if applicable) of each of these 34 official Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume Faculty colors have been noted. Also included on this chart are six recent Faculty colors that – with one exception – were not approved by the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume or the American Council on Education, but may nonetheless have some claim to legitimacy because they were adopted by academic professional organizations. The American Occupational Therapy Association Commission on Education selected slate blue for the Master and Doctor of Occupational Therapy degrees in 1995; the Board of Directors of the American Physical Therapy Association approved teal for the Master and Doctor of Physical Therapy degrees in 1997; the National Association of Future Doctors of Audiology selected spruce green for the Doctor of Audiology degree in 2001; a year later the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences adopted midnight blue for degrees in Criminal Justice; the National Council of Schools and Programs of Professional Psychology selected royal blue for the Doctor of Psychology degree in 2007; and in 2009 bilberry was chosen by the Interior Design Educators Council as the academic color for Interior Design. Unfortunately the Faculty colors for Audiology and Physical Therapy are easily confused with each other and with the color shades the Intercollegiate Bureau already approved for degrees in Optometry and degrees in Podiatry. Likewise, the bilberry of Interior Design is too similar in color to the purple of Laws, and the midnight blue of Criminal Justice is almost identical to the dark blue of Philosophy.

Agriculture

Arts, Letters, Humanities

Audiology

Commerce, Accountancy, Business

Criminal Justice

Dentistry

Economics

maize

c. 1910 –

white

1895 –

spruce green

2001 –

drab

c. 1903 –

midnight blue

2002 –

lilac

c. 1898 –

copper

c. 1912 –

Education, Pedagogy

Engineering

Fine Arts, Architecture

Foreign Service, Public Administration

Forestry

Home Economics

light blue

1903 –

orange

c. 1906 –

brown

1895 –

peacock blue

c. 1957 –

russet

c. 1900 –

maroon

1961 –

Humanics

Interior Design

Journalism

Laws

Library Science

Medicine

Music

crimson

c. 1910 – 1959

bilberry

2009 –

crimson

1959 –

purple

1895 –

lemon yellow

c. 1901 –

green

1895 –

pink

1895 –

Naprapathy

Nursing

Occupational Therapy

Optometry

Oratory, Speech

Pharmacy

Philanthropy

cerise

c. 1959 – 1960?

apricot

c. 1937 –

slate blue

1995 –

seafoam green

1949 –

silver gray

c. 1906 –

olive green

1901 –

rose

c. 1936 – 1959

Philosophy

Physical Education

Physical Therapy

Podiatry, Surgical Chiropody

Political Science

Psychology

dark blue

1895 –

sage green

c. 1910 –

teal

1997 –

Nile green

c. 1936 –

royal blue

c. 1957 – 1959?

royal blue

2007 –

Public Health

Retailing

Science

Social Science

Social Work, Social Service

Theology, Divinity

Veterinary Science

salmon pink

c. 1915 –

turquoise

c. 1957 – 1959?

golden yellow

1895 –

cream

c. 1960 –

citron

c. 1937 –

scarlet

1895 –

gray

1901 –

In most cases, the colors in this chart have been matched to vintage velvet hood fabric by the Cotrell & Leonard company, which was the “depository” for the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume. It should be observed that in actual practice the Intercollegiate Bureau and Cotrell & Leonard used darker shades of these Faculty colors than the color descriptions might imply, so that if they were used for the velvet facings and sleeve bars of a doctoral gown the contrast between the black gown and the Faculty color would not be too extreme. Many of these colors had symbolic associations with the degree Faculty.

By the 1950s a significant problem had slowly wormed its way into the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume’s approach to assigning Faculty colors. Instead of using a given Faculty color to represent a range of related degree titles (as the 1895 Intercollegiate Commission on Academic Costume had envisioned), the Bureau had fallen into the habit of assigning individual Faculty colors to very narrow and specific degree titles or Faculties. For instance, individual Faculty colors were assigned to the Doctor of Dental Surgery, Master of Nursing, Doctor of Optometry, Doctor of Pharmacy, Doctor of Podiatry, Doctor of Public Health, and Doctor of Veterinary Medicine degrees when the green of Medicine could have stood for all. The Bureau assigned sage green to Physical Education even though light blue already existed for Education. Cumulatively the excessive multiplication of Faculty colors in the Intercollegiate Code made it difficult to distinguish between (and remember) some of the Faculty colors. The seafoam green of Optometry and the blue-green shade of Nile green the IBAC used for Podiatry were easily confused (Nile green is actually a yellow-green color), and later the colors professional organizations adopted for Audiology (spruce green) and Physical Therapy (teal) only compounded this problem. Especially troublesome were the similar reddish-brown hues assigned to Economics, Forestry, Home Economics, Humanics, Journalism, and Philanthropy.

For example, on the right is a photograph of a doctoral hood from Johns Hopkins University in the 16 October 1950 issue of Life magazine. Does the velvet edging of this hood represent a Doctor of Engineering (orange), Doctor of Nursing (apricot), or Doctor of Social Work (citron) degree? The answer is that this hood represents none of these degrees. This hood is meant to indicate a Doctor of Public Health (salmon pink) degree. The company that manufactured the hood is not identified, but obviously they were using a shade of “salmon pink” that was inconsistent with the hue intended by the Intercollegiate Bureau.

Not only had new Faculty titles multiplied at a rapid pace, tagged degrees began to become more common in the 1930s as a way of indicating the major subject of a traditional liberal arts or research degree like the Master of Science. Understanding the pedagogical difference between the liberal arts or research degrees and the professional, vocational, or technical degrees; recognizing how the nomenclature of these two types of degrees was distinctive; and wanting to preserve these differences in the Faculty color system of American academic costume, the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume treated tagged degrees like the liberal arts or research degrees they were, and continued to make the Faculty of the degree determine the Faculty color, not the subject. The hood, the Bureau wrote in 1948, should be

bordered with velvet or velveteen of the proper width to indicate the faculty. The reading of the degree, and not the department in which the major work was done, governs the proper color of the border. Thus, a degree conferred as “Bachelor of Science in Engineering” requires the gold yellow of Science whereas “Bachelor of Engineering” requires the orange border of Engineering.

This pedagogically sound approach, entirely consistent with the stipulations of the 1895 Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume, did not please everyone. So with the Intercollegiate Bureau’s help, the American Council on Education, a professional association of college and university presidents, updated the 1895 Intercollegiate Code between 1932 and 1935, calling it the “Academic Costume Code”. While otherwise a fine update of the 1895 Intercollegiate Code, the Council’s 1935 Academic Costume Code unfortunately introduced an element of Faculty color ambiguity that was inconsistent with the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume’s approach: for the American Council on Education, the Faculty color could indicate either the Faculty or the subject of a tagged degree.

The American Council on Education’s 1960 update of their Academic Costume Code marked a complete rupture with the Faculty color system of the 1895 Intercollegiate Code. With the tacit approval of the Intercollegiate Bureau (which was beginning to abdicate most of the responsibilities it had been given by the 1895 Intercollegiate Commission on Academic Costume), the American Council on Education made the major subject of the degree determinative of the hood’s velvet edging color, not the nomenclature of the degree. The Intercollegiate Bureau’s Faculty colors were now to be considered “subject colors”, and the wording of the degree on one’s diploma was to be ignored. The American Council on Education’s approach unfortunately obscured the differences between liberal arts or research degrees and professional, vocational, or technical degrees, so that a Master of Science degree in engineering, a Master of Science in Engineering degree (both liberal arts or research degrees), and a Master of Engineering degree (a professional, vocational, or technical degree) used the same subject color: orange.

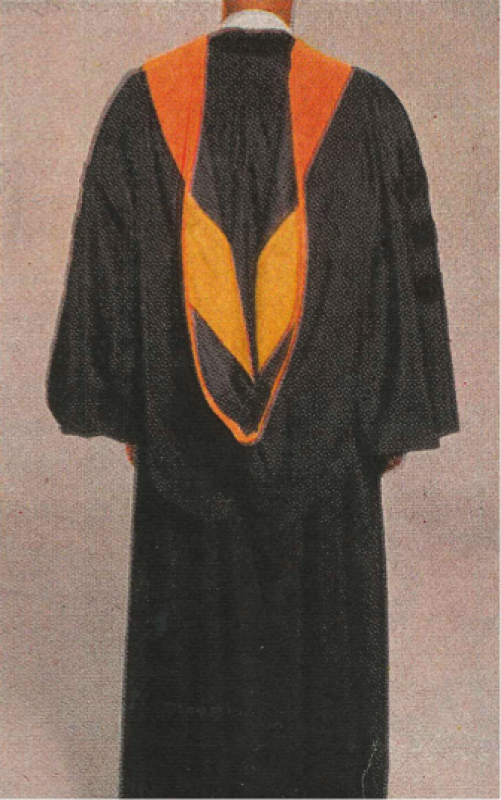

In the photo to the right, two hoods from the archives of Emmanuel Christian Seminary (now part of Milligan University in Tennessee) illustrate this problem with the “subject color” approach of the 1960 Academic Costume Code. The hood on the left is for a tagged “Master of Arts in Religion” (research) degree, and the hood on the right is for a “Master of Divinity” (professional) degree. The “subject color” approach of the Academic Costume Code would have made the hoods indistinguishable because both would have been edged with scarlet, for Theology. But the seminary wanted to signify the difference between the two degrees, so they had hoods for the Master of Arts in Religion degree tailored with divided edging in white (Arts) and scarlet (Theology). This modification runs counter to both the Academic Costume Code and the Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume; the latter stipulates the hood for the Master of Arts in Religion degree should be edged with white, only.

How the 1960 Academic Costume Code was supposed to indicate the subject of the degree rather than the title of the degree can be seen in the photograph on the left, from a 1966 E.R. Moore catalogue. Hood #1, at the bottom of the photograph, was for a “Master of Agricultural Education” degree and had a maize-colored velvet edging (for Agriculture). But light blue (for Education) would have been an equally acceptable option. Hood #7 was for a “Master of Science” degree in Public Health Nursing. Here the velvet trim was apricot (for Nursing), but salmon pink (for Public Health) could have been a legitimate choice. The 1960 Code made golden yellow (for Science) incorrect. Hood #13 was for a “Master of Science” degree in Physical Education and used sage green velvet (for Physical Education), not golden yellow (for Science). For the same reason the “Bachelor of Science” hood in Aerospace Engineering (hood #14) used orange (for Engineering) and not golden yellow. The pink velvet on Hood #16 indicated a “Master of Arts” degree in Music; white (for Arts) would have been incorrect according to the 1960 Code.

The current version of the Academic Costume Code, last revised in 1987, uses a slightly shorter list of official subject colors than the Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume because the American Council on Education did not approve a few of the Intercollegiate Bureau’s pre-1960 Faculty colors and has not authorized any new subject colors since 1961, leaving many academic subjects without a color unique to their discipline. So for example, while Journalism was fortunate to be assigned crimson in 1959, other mass media subjects have been abandoned without a color. As a result, a number of unauthorized subject and Faculty colors have been used over the years as a way of signifying a particular academic subject on one’s academic hood edging or doctoral gown trim, often duplicating an authorized Faculty or subject color or creating a hue indistinguishable from or easily mistaken for an authorized Faculty or subject color.

An example of this pernicious tendency can be seen on the hood to the right. It is a hood for a Doctor of Chiropractic degree from Sherman College of Chiropractic in Spartanburg, South Carolina, manufactured in 2011 by the Herff Jones company. The hood is edged with “silver” (light gray) velvet. “Silver gray” (also light gray) is the Faculty color the Intercollegiate Bureau assigned to Oratory (or Speech) around 1906, but a century later some colleges and universities have begun using “silver” as the Faculty or subject color for Chiropractic. This distinction without a difference makes it difficult to know what degree or subject a hood edged with light gray velvet represents without asking the wearer.

It should be clear that the “subject color” approach of the 1960 Academic Costume Code required individual institutions or degree recipients to subjectively determine the “best” subject color to use when a subject lacked an official color. This introduced a great deal of ambiguity into the semiotics of American academic costume. For example, to the left is a photograph of an Ohio University Doctor of Philosophy hood for a 1961 dissertation in “speech and hearing therapy”. Under the 1895 Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume, the velvet edging for this hood would have been dark blue, the degree color assigned to “Philosophy”, making it easy to read the hood as that of a “Doctor of Philosophy”. But now that the 1960 Academic Costume Code had made the major subject of the degree determine the color of the velvet trim of the hood, one’s degree title was irrelevant. Unfortunately, in this case neither the American Council on Education nor the Intercollegiate Bureau of Academic Costume had created a subject color for “speech and hearing therapy”. So what subject color was appropriate? In this case, Ohio University decided that the subject color for this hood should be white, the color the 1960 Code assigned to majors in “Arts, Letters, Humanities”. One can only guess why the university selected white, as silver gray (“Oratory/Speech”), golden yellow (“Science”), green (“Medicine”), or salmon pink (“Public Health”) were available subject color categories in the 1960 Code. Thus the hood becomes impossible to read with any kind of semiotic precision, except to say that it is a hood for a doctoral degree of some sort.

An article by Stephen Wolgast in 2011 and a series of articles by Kenneth Suit in the 2015, 2017, and 2020 Transactions of the Burgon Society address this complicated history of American Faculty colors in more detail, but the sad fact of the matter is that today the system is in complete disarray, unable to function as the authors of the 1895 Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume intended. There are competing lists of Faculty and subject colors, and there is no consistency to the way American academic colors are employed: some colleges, universities, academic costume manufacturers, and consumers use the “Faculty color” stipulations of 1895 Intercollegiate Code of Academic Costume, while others use the “subject color” stipulations of the 1960 Academic Costume Code. A renewed commitment to a standardized system is desperately needed to resolve the confusion the current disorder has created.

A proposed solution to these problems is discussed here.